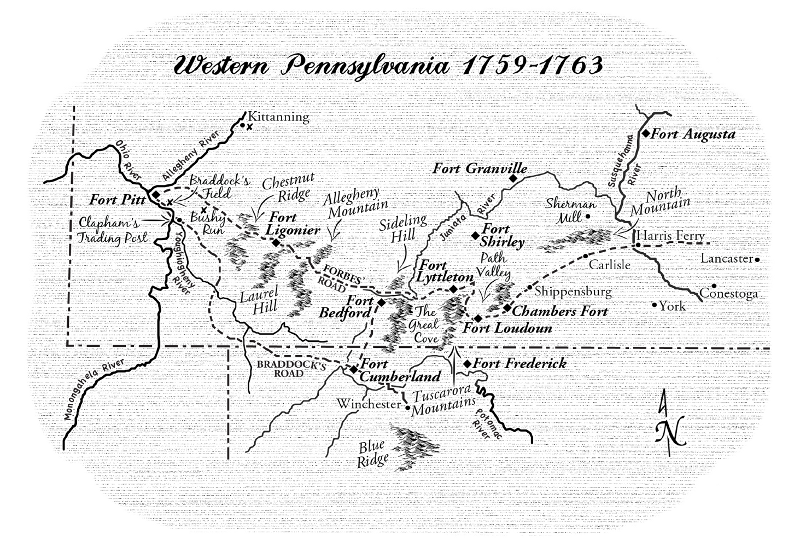

Western Pennsylvania

Hot Spot of Colonial History and Warfare

In the middle decades of the 18th century, no area of North America was more in the spotlight than the junction of three rivers—the point where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers join to form the Ohio River. This strategic area, called the Forks of the Ohio, was the cradle of the French and Indian War. In the immediate aftermath of that war, it was also an important focus of Pontiac’s Rebellion, and thus the scene of much of the action in the novel Forbes Road.

Links to Historical Sites along Forbes Road

Opening of French and Indian War

In 1753, Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia learned that the French were moving into the Ohio Country and setting up forts and trading centers along the Allegheny River. Since the area was claimed by Britain, he determined to send an ultimatum demanding that France withdraw. He chose young militia major George Washington as his emissary. Subsequently, in 1754, faced with the rejection of his demands by the French, and their construction of Fort Duquesne at the forks, Dinwiddie sent Washington back in command of a military force to show British determination to hold Western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Country. The show of force escalated into combat and the defeat of Washington’s command at tiny, hastily constructed Fort Necessity. The incident ignited the French and Indian War (Called the Seven Year’s War outside of North America).

The Braddock Disaster

In response, Britain sent, in 1755, two regiments of regular infantry, provincial militia, and supporting units under Major General Edward Braddock to wrest the Forks of the Ohio from France. At 2500 men overall, this was the largest military expedition that the English had ever assembled in the North American colonies and was intended to secure the frontier country from Virginia up to the Great Lakes. Braddock marched from Alexandria, Virginia to Fort Cumberland in Maryland. Then, with great determination, his army cut a road through the forest and over several mountain ridges to the vicinity of Fort Duquesne. However, shortly after crossing the Monongahela River, the British advance force, numbering about 1500 regulars and provincials, met a force of about 600 French soldiers, militiamen, and Indians. Although frequently described as an ambush, the action was actually a meeting engagement wherein two advancing forces clashed. The British were defeated because Braddock’s men used classic European linear tactics against experienced forest warriors. After the battle, as Braddock lay dying, his last words were, “We shall better know how to deal with them another time.”

British Restructuring

In the aftermath, the British army concentrated on learning to fight in the forest. They developed new units including provincial regiments, light infantry, and rangers. Every battalion was expanded to include a light infantry company, and an entire regiment of light infantry, the 80th Foot, was organized. Among the innovations was establishment of the 60th Foot, or Royal American Regiment. This unit was designed to man forts in the border country and fight in the wilderness. The new regiment was officered by professional military officers from across Europe, including many Swiss. Among these was Lieutenant Colonel Henry Bouquet, a farsighted and innovative officer who eventually to become commander of the regiment’s first battalion. The government also deployed three highland regiments—the 42nd Foot, or Black Watch, the 77th Foot, Montgomeries’ Highlanders, and the 78th Foot, Fraser’s Highlanders. The British considered them a form of light infantry and also recognized that the highlanders’ facility with cold steel made them a match for the tribal warriors in close combat. Equipment was modified for the new conditions, including shortening muskets, adopting the hatchet as a hand to hand weapon, and introducing the rifle to some army units. Many regiments modified their uniforms to make them more suitable for frontier warfare—providing short jackets, tan or brown breeches, broad-brimmed hats, leggings, and sometimes moccasins. New tactics were also developed—the order, “To Trees!” meant for soldiers to break ranks and fight individually.

French and Ohio Tribes Strike Back

While the British military was restructuring, the French and their Native American allies took the offensive. In 1755-56, war parties, often operating from Fort Duquesne and the Delaware tribal town of Kittanning, swept through Pennsylvania, sometimes striking as far eastward as the Susquehanna. In one major strike, fifty-five people were killed in the Great Cove of Pennsylvania (See map above). The outcry of settlers from these devastating attacks forced the government of the colony, controlled by pacifist Quakers, to finally take measures to protect the frontier country. A provincial regiment was raised and a defense line of several forts, including Loudoun, Lyttleton, Shirley, Granville, and Augusta, was constructed.

The Forbes Campaign

Credit: 'The Royal Americans' by Pamela Patrick White

By 1758, the British were ready to resume theatre-wide offensive operations. In Pennsylvania, the objective was to finish what Braddock had attempted—capture of Fort Duquesne and The Forks of the Ohio. Major General John Forbes, with a force of 6,000 regulars and provincial troops, was assigned this task. Most people assumed he would use Braddock’s Road to approach Duquesne. But Forbes, an intelligent and competent officer, determined to cut a new, more direct road through Pennsylvania, crossing Sideling Hill, the Allegheny Mountains, and the Laurel Highlands. As in most military campaigns, logistics dictated the decision—Pennsylvania was a better source of wagons, horses, drivers and supplies than more thinly settled Virginia. In the spring of 1758, as the army was about to begin its westward march, a complication arose—Forbes was smitten with what contemporary writers called a “wasting” disease, probably some form of cancer. The general rapidly weakened and was forced to delegate much work of the campaign to his deputy—Colonel Henry Bouquet. In fact, the two men became a highly effective team—Forbes conducting planning in the rear and Bouquet the forward area tactical leader who made things happen.

In cutting the wilderness trail which would become Forbes Road, the general ensured that several way-stations were built which could serve as supply depots and rallying points in case of a tactical reverse. Chief among these were Fort Bedford and Fort Ligonier. Ligonier, less than fifty miles from the Forks of the Ohio, would be the jumping-off place for the final advance against Fort Duquesne. In October, while Ligonier was under construction, Bouquet authorized Major Grant of the 77th Foot to lead a reconnaissance against Duquesne, in an effort to determine the enemy’s force and the strength of the fortifications. Ignoring the colonel’s orders, Grant turned the 800 man scouting expedition into an attack, and suffered a devastating defeat in which over half of his force was lost and Grant himself was captured.

But this reverse set in train a sequence of events which eventually led to British victory. The French commander at Duquesne sent a reconnaissance force of his own to Ligonier. What this scouting party found was that enemy strength was far greater than the French had thought possible. Realizing that resistance was futile, the French blew up their fortress and retreated. Forbes’ army marched to the forks and occupied the ruins of Duquesne without further conflict. The general then ordered a great fortress built on the site and named it after William Pitt, the prime minister of Great Britain. The dying Forbes then traveled back to Philadelphia, where he expired only a few months after the destruction of Fort Duquesne.

Pontiac’s Rebellion

Two years later, as 1760 ended, Britain had essentially defeated France in North America and seized control of her former possessions. However, the Ohio Country tribes watched the expansion of British control with great concern. They were infuriated by broken treaties, the string of forts built along the Allegheny and into the Great Lakes region, and the influx of settlers. Moreover, the chiefs were antagonized when the British ended the French practice of providing annual gifts. Tribal unrest was increased by the teachings of a fundamentalist Delaware mystic named Neolin, often called “The Prophet.” He preached that all the tribes should unite in war to drive out the Europeans, then discard the tools, weapons, and other amenities introduced by the white men and revert to the Indians’ traditional way of life. He was joined in the call to war by an influential Ottawa leader called Pontiac and a Mingo war captain named Guyasuta.

In the spring of 1763 an alliance of tribes from the Great Lakes down to the Forks of the Ohio rose in revolt. A coordinated surprise attack destroyed eight of eleven British forts in the region. Forts Detroit and Pitt were placed under siege by massive forces. Then war parties attacked deep into Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Maryland, destroying farms and settlements. Hundreds of settlers were killed or captured.

The Fort Pitt Relief Expedition and the Battle of Bushy Run

Credit: 'The 77th At Bushy Run' by Pamela Patrick White

In Pennsylvania, some 650 settlers and soldiers were held under siege in Fort Pitt by a strong force of Delawares, Shawnees, Wyandots, and Mingoes. Conditions in the fort became desperate: Flour in the storehouses had spoiled, flooding of a magazine had ruined the majority the gunpowder, and smallpox had broken out. General Amherst directed Colonel Bouquet to organize a relief column which would march from Carlisle to the Forks of the Ohio through 200 miles of hostile wilderness. But British military forces in the colonies had been drained off to attack French possessions in the West Indies—Amherst was could assign only 450 soldiers to Bouquet’s command. Most of these were detachments of two highland regiments—the 42nd Foot (Black Watch) and 77th Foot—which had been devastated by yellow fever during operations in the Caribbean. Many of the men were still so weak that they had to be transported in wagons. Moreover, the 77th had been scheduled to be disbanded and sent back to Scotland, so its organization was in turmoil. But Bouquet was uniquely qualified to lead the relief. He had been the military commander in Pennsylvania for five years, had built Forbes Road, and most importantly, had been focused on conducting forest warfare since the end of the Forbes campaign. He had developed his own combat tactics and formations.

Bouquet marched in late July with his soldiers, a herd of livestock, and 32 wagons carrying provisions for the fort. As the expedition traveled along Forbes Road, he spent time training the highlanders in the forest warfare. At Fort Ligonier, Bouquet transferred the most vital supplies to 340 pack horses to enable more rapid and agile movement. He anticipated that the tribal force would attack in the area of Turtle Creek, a valley of a narrow defiles which would favor an ambush. To counter this, he planned to march rapidly to Bushy Run Station, located near the Turtle Creek area and go into camp as if he intended to remain over-night. He would then break camp and steal through the Turtle Creek valley in the dark of night. However, the opposing forces actually met in battle on August 2nd, about a mile before Bushy Run. The battle opened with war parties on a high ridge firing down upon the advancing column. The British light infantry immediately charged and drove the Indians off the hill. But the tribal force, probably numbering around 400, spread out and enveloped the convoy. The battle then became a confused, soldiers’ battle—small groups on either side engaged in vicious combat among the trees and brush. Toward evening Bouquet had soldiers and pack horse drovers use flour bags to construct a small, circular stockade on a rise he called Edge Hill, to shelter the wounded. Then, at dusk, the British force formed a perimeter around the fort and settled in for the night.

As Bouquet took stock, it became clear that although the highlanders had fought magnificently, the expedition was in a tough spot. There were forty-plus dead, another fifty wounded, and most of the pack horses had been killed or run off. With no transport, attempting to push ahead was impossible and a retreat toward Ligonier would have resulted in a disastrous running fight. Bouquet’s only option was to destroy or chase off the Indians. So he developed a daring all-or-nothing tactical plan. The next morning, after tribal attacks began again, two companies feigned a panic stricken withdrawal to Forbes Road and then ran eastward, making it look like the start of a retreat toward Ligonier. Other companies closed the gap in the perimeter and fell back as if they were getting ready to join the retreat. As Bouquet had hoped, the majority of warriors charged the improvised fort in a tightly packed mass. Just as it looked like they would overwhelm the British, the first set of companies reappeared on the Indians’ right flank, having taken advantage of a low ridge and trees to cover their movement. They fired several volleys of musket fire into the concentrated Indian attackers and then charged with the bayonet. The surprised warriors broke and ran westward, leaving their dead on the field. As they ran, another two companies of highlanders advanced from the perimeter and fired several volleys into the Indians, which completed the route. Bouquet’s column was able to continue its march and relieve Fort Pitt. The Indians retreated to their villages in the Ohio Country, their confidence shaken by their first loss to British regulars.

Bouquet Marches into the Ohio Country

Bouquet’s victory at Bushy Run in 1763 laid the foundation for a successful, and essentially bloodless, expedition into the Ohio Country in 1764. The force consisted of the Black Watch and several battalions of provincial troops and militia, the majority from Virginia. As the colonel had anticipated, the tribal leaders were impressed by the size of his force—over 1500 men—and determined that negotiation was the better part of valor. They met with Bouquet on the Muskingham River and agreed to peace terms which included handover of European hostages. Bouquet returned to the universal gratitude of the colonists and King George III. Pennsylvania rewarded him with a resolution of thanks and a large land grant. King George personally made the decision to promote Bouquet to Brigadier General, an unprecedented honor for a foreigner in British service. Along with his promotion, Bouquet was assigned command of British forces in the southern colonies. Then, at the height of his career, misfortune overtook him. He took ship for his new headquarters in Pensacola in 1765; enroute the vessel stopped in Havana and Bouquet contracted yellow fever. He died onboard the ship on September 2, 1765 while at anchor off Pensacola. The general’s unmarked grave is somewhere below the modern streets of that city. But this much can be said of Henry Bouquet: In the decade before the American Revolution, his record undoubtedly made him the most respected military officer in the colonies. By contrast, the record of that ambitious young Virginia officer, George Washington, was considered mixed at best.